Thermal Conceptual Metaphors

A study of metaphorical meanings associated with thermal sensations in an interactive context

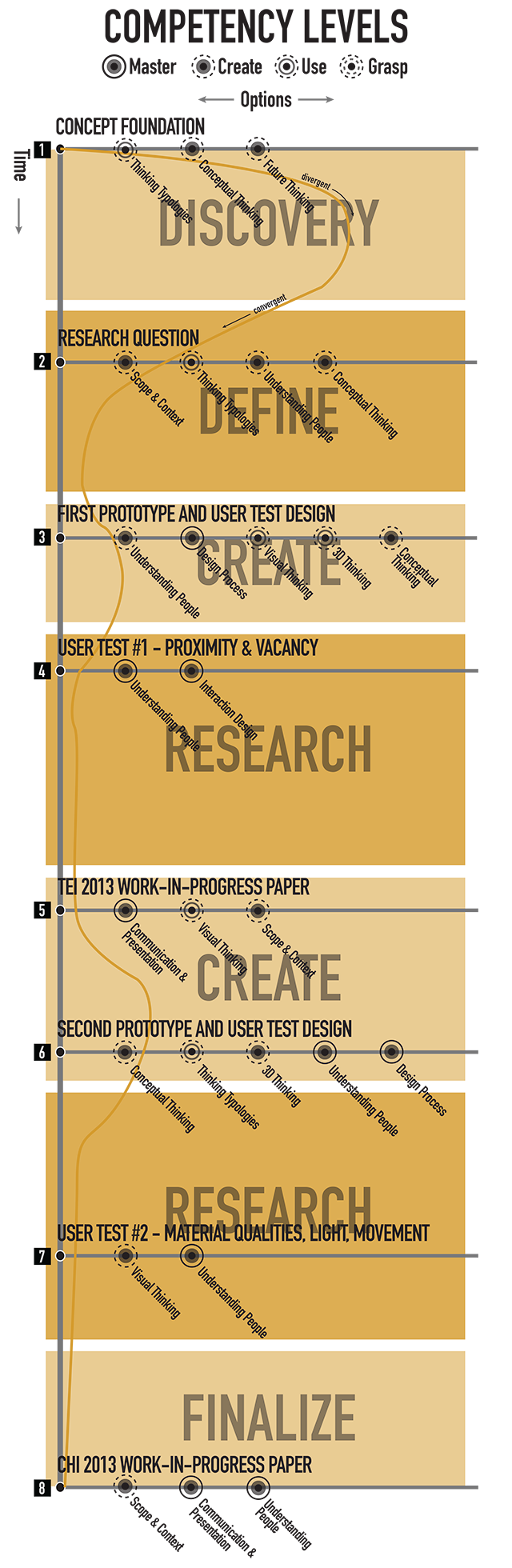

Design Process

Our studies leading into the project looked at two studies by Lee and Lim (see papers for sources) on “thermal expressions” (thermal sensations delivered through a wearable device). However, their study focused on an ambiguous context in which they observed meanings that emerged for the participants when given a device with a wide range of thermal sensations that could be sent to others (magnitude of heat or coolness, differing intensities and rates of change, etc…) They found that people invented their own meanings for the sensations based on their own biases towards feeling different kinds of warm and cool sensations, and the recipients often did not understand the intended meaning.

Meanwhile, we also read about “conceptual metaphors”, defined by Lakoff and Johnson as “the essence of understanding one kind of thing in terms of another” and said to be core to human experience as a whole. The power of understanding something in terms of something else is found throughout interaction and language, thus making it very powerful, and very useful. This led us to forming our research question, essentially asking “What kind of meanings in interaction can be understood in terms of temperature?”

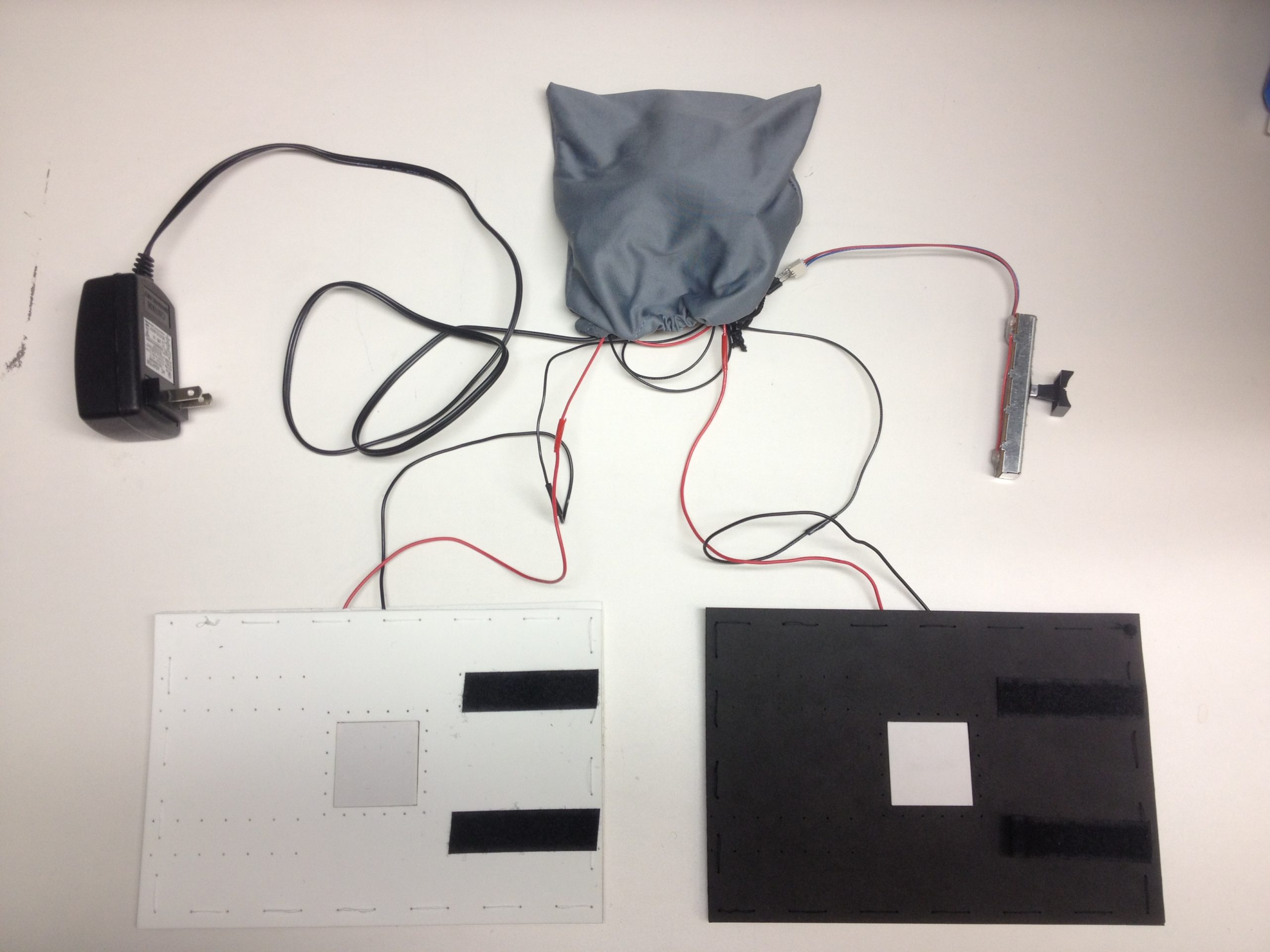

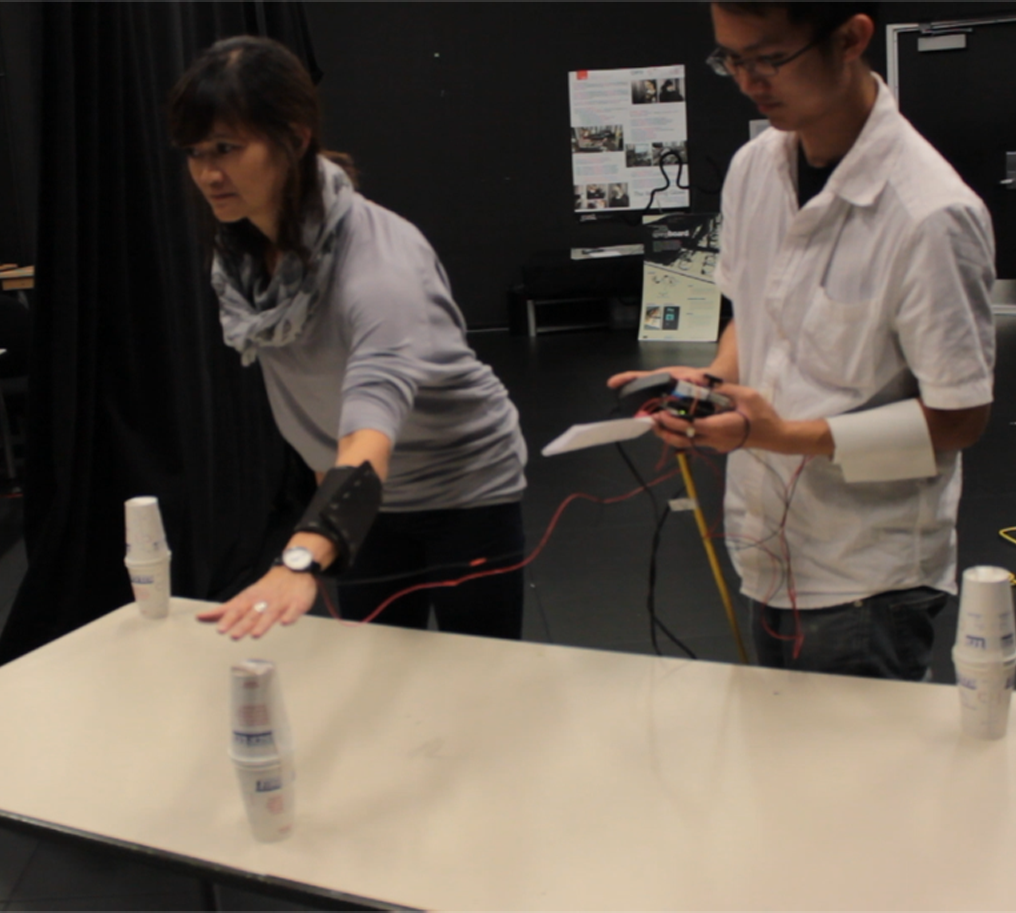

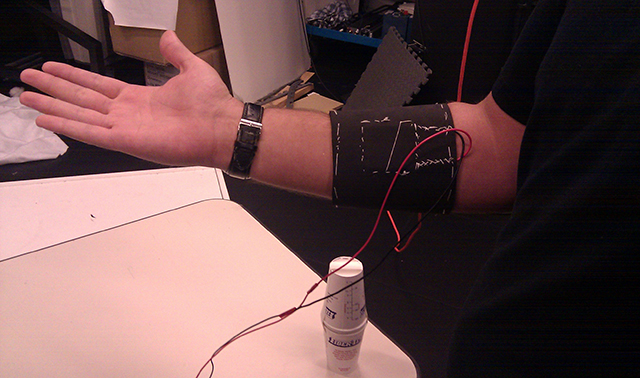

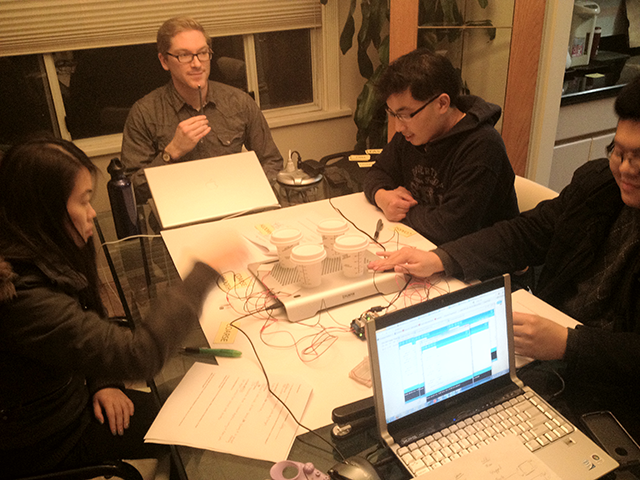

To answer this question, we designed an experiment to test the theory. We designed a wearable device that can deliver thermal feedback, similar to Lee and Lim’s prototype, which used a slider and button combo to send signals to a Peltier plate. With it, we tested 25 participants’ interpretations of proximity (close/far) and vacancy (empty/full) in terms of temperature. We tested each metaphor with a set of tasks (find or avoid a hidden object; choose a covered cup that is full or empty for vacancy), each having the wearable prototype signal them with warm or cool sensations at the appropriate time.

In order to conclusively state that a specific meaning was being interpreted by the participants, we used a mixture of standard metaphors (warm = close, cool = far, warm = full, cool = empty) and inverse metaphors (inverted meanings, warm = far, etc), and randomized the task order for different participants, to compensate for learning effects (experience of doing previous task informs participants of how the next will work if it is not randomized). This way, we knew that the meanings interpreted related to the intended context (proximity and vacancy), instead of the goal (warm = good, positive, closer to goal, cool is opposite, etc), so when we tested warm = far, participants that still interpreted this as “close” were interpreting the sensation in terms of proximity, for example.

We found that for all 25 participants, the proximity metaphor was interpreted the same way no matter how it was set up (inverted, reversed task order, etc). The vacancy metaphor, on the other hand, was close to a 50-50 split, showing that the proximity metaphor has potential for use in interaction design, but the vacancy metaphor does not. We speculated that common shared experiences throughout life for proximity (playing the “hot and cold” game, experiencing warmth radiating from a heat source, but not the opposite) create this effect, while no such unifying experiences exist for vacancy. Our findings were used to write the work in progress paper for the TEI 2013 conference in Barcelona, which was accepted.

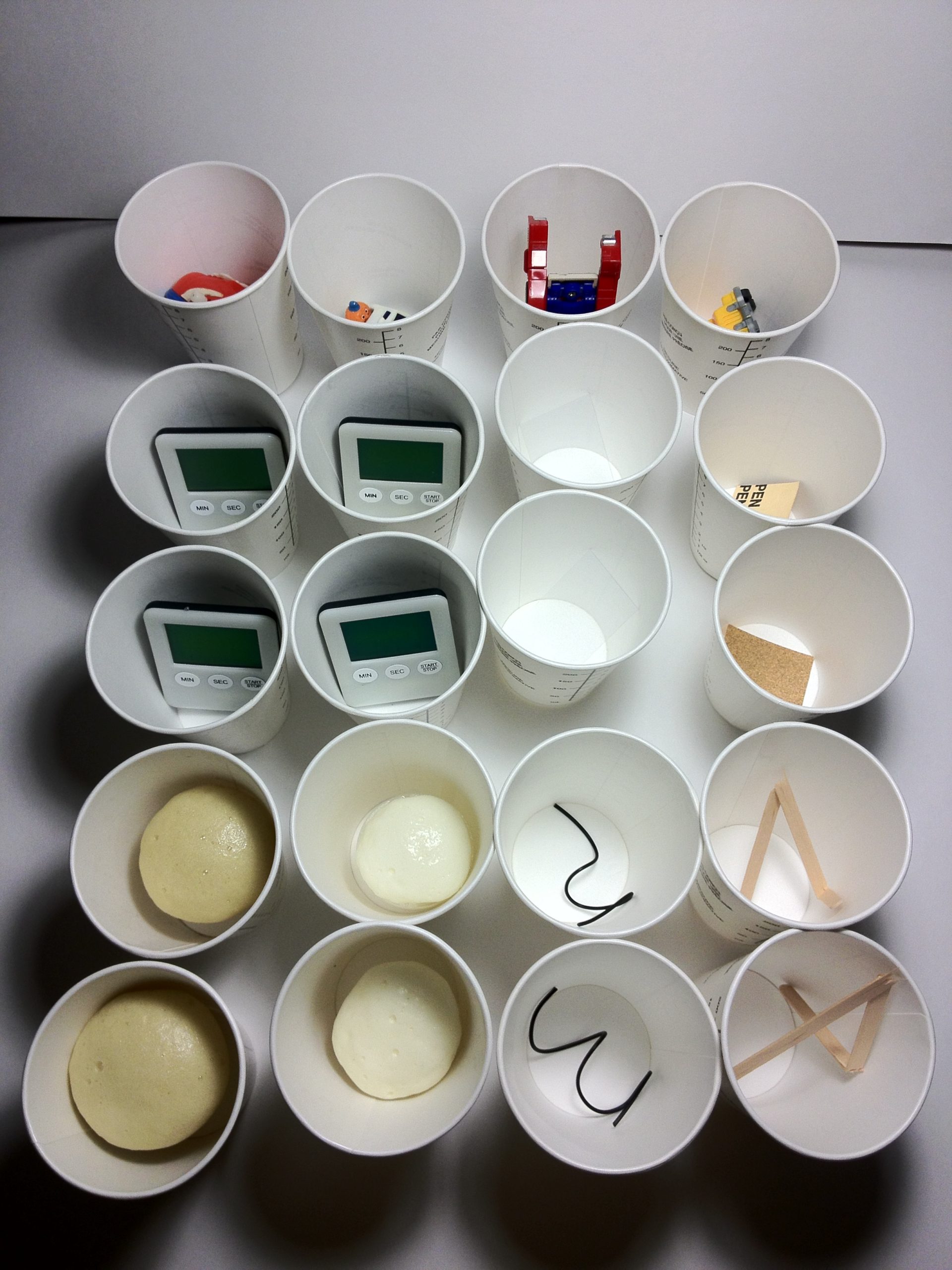

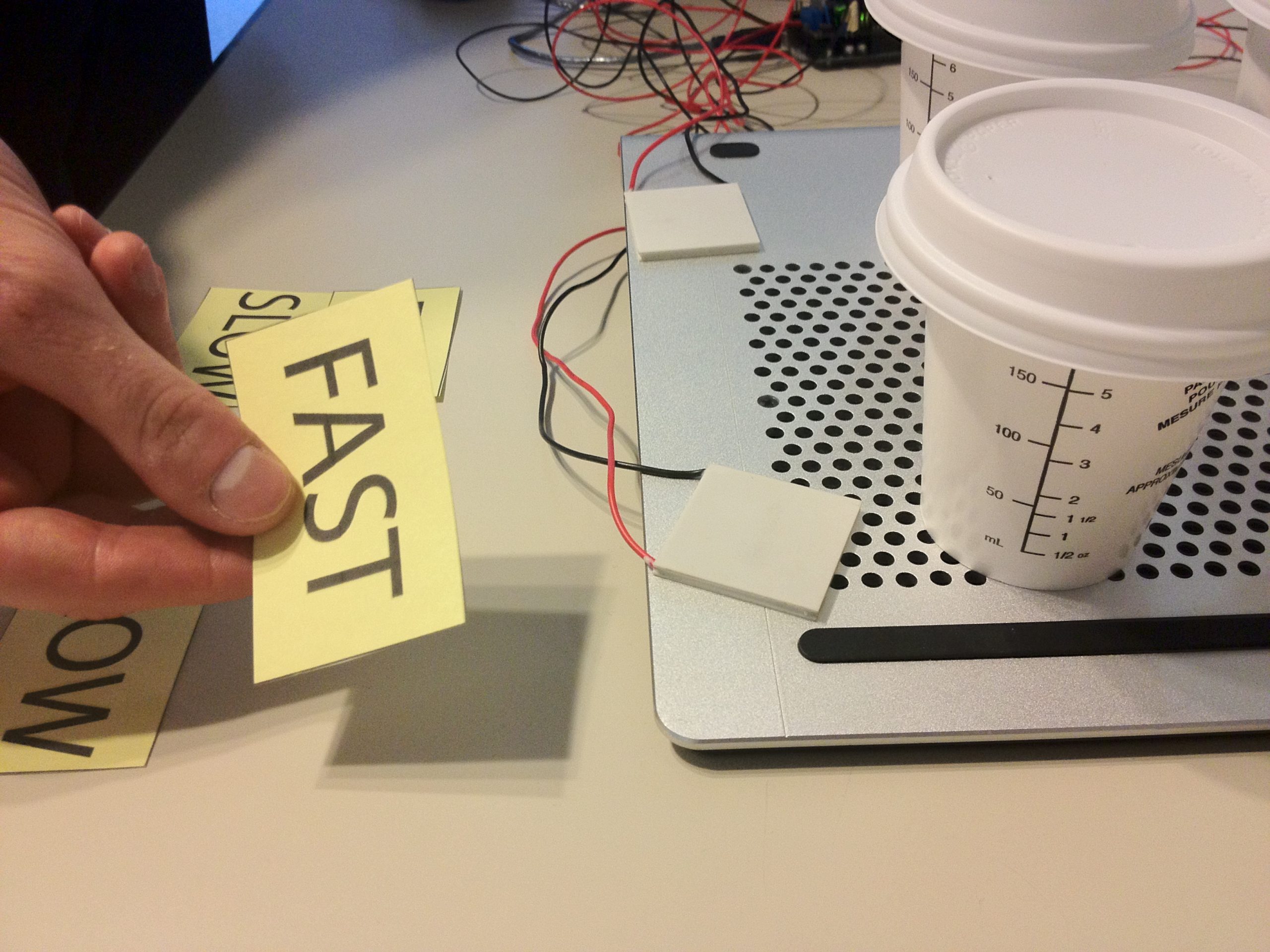

For the next phase, we focused on finding additional workable metaphors, so we designed a second experiment that took less time and used fewer resources, but lacked the wearable aspects of the prototype. To simply test peoples’ interpretations of metaphors in a specific context, we had many participants touch Peltier plates, and decide between two contrary adjectives (soft/hard, flexible/brittle, coarse/smooth, etc) depending on whether they felt a warm or cool sensation. To make it more interesting for the participants, we designed objects that were placed inside covered cups that embodied each adjective, so the participants could see (or touch) for themselves whether or not they got it right (there were inverse metaphors in this experiment, just like the previous ones, so we intended for participants’ interpretations to possibly not match).

This experiment was less complex, since there were no tasks, only directly interpreting the meaning of the thermal sensations. With such a simple setup, we were able to get more results, and much more quickly. Of six metaphors, we found that only three had significant agreement among the participants (80% or more), but two others were just short of that. One was around 50% (warm is coarse, cool is smooth), which corresponded with our expectations prior to the experiment.

As a result, we were able to report in our paper that, as Lakoff and Johnson discussed, the more common experiences in everyday life correspond with contextual associations that are expressed as metaphors, the more likely it is for that metaphor to work as a mapping for

interactions. The work-in-progress paper about this study was accepted to CHI 2013 in Paris.

interactions. The work-in-progress paper about this study was accepted to CHI 2013 in Paris.

Results

- Independant Academic Research

- July 2012-January 2013